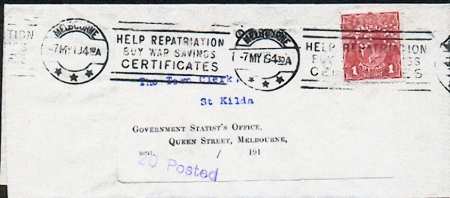

This long envelope was sent from The Town Clerk, St. Kilda. Melbourne to the Government Statist’s Office, Queen Street, Melbourne. It has an OS perfined red 1d KGV head stamp. It is postmarked with a roller cancel, MELBOURNE/ -7 MY 19 430A with the slogan HELP REPATRIATION/ BUY WAR SAVINGS/ CERTIFICATES, and there is a purple hand-stamp of ‘20 Posted’. The reverse was not seen, but the contents are given by the vendor that ‘628 people died in Melbourne in the first quarter of 1919′ (Figure 1).

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed more people than in World War I, at somewhere between 20 and 40 million people. It has been cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history. More people died of influenza in a single year than in four-years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351.

With the outbreak of Spanish Influenza in Melbourne in December 1918, people were advised not to panic. Earlier, local authorities were aware of the disease in Europe and its devastating effects upon the population so strict procedures had been put in place in order to limit its impact. As a consequence Melbourne escaped relatively lightly compared to the number of deaths in Europe and America. Although named ‘Spanish Influenza’ its origin was not in Spain but in United States of America. Eventually it moved to the general population and spread throughout the world.

The disease struck with amazing speed, overwhelming the body’s natural defences, causing uncontrollable hemorrhaging that filled the lungs, resulting in the victim drowning in his or her own body fluids. Individuals who were healthy in the morning were dead in the evening. Not only was it strikingly virulent, it attacked the young healthy adults rather than, as might be expected, the very young, the very old and the infirm. This was a reversal of the normal mortality pattern.

While the Melbourne Argus, in November 1918, was tracking the progress of the disease and resulting deaths in Sydney, no similar outbreak was evident in Melbourne. Nevertheless people were being advised to take precautions. Dr William McClelland, the medical officer for Brighton, proposed in early December to establish an auxiliary hospital in the Wilson Recreation Hall, with one ward each for males and females. By February 22, 1919 the hospital was established and Nurse Powell was appointed as matron to be assisted by VAD nurses.

It was in January 1919 that Victoria was declared infected and the State placed in quarantine with theatres and schools forced to close. The outbreak was first recognized on January 21, 1919.

People were encouraged to wear masks in shops, hotels, churches and public transport. Public meetings of twenty or more people were prohibited and travel in long distance trains was restricted. The New South Wales government closed the border with Victoria prohibiting traffic between the states. Where a member of a family was infected, the house was isolated and quarantine rules were applied.

Local doctors implemented a program of inoculation at local centres with several hundred people taking advantage of this service. Nevertheless there was not universal acceptance amongst members of the community of inoculation as a means of preventing infection or restricting the progress of the disease.

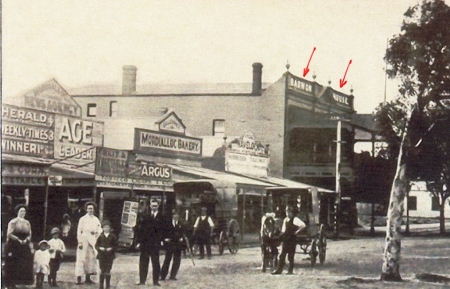

When the Moorabbin Shire Council established an auxiliary hospital at Barwon House in Mordialloc great indignation was expressed by some members of the community because of its location right in the centre of the town. Protesters, at a meeting organised by the Mordialloc Progress Association and held at the Mechanics’ Institute, argued that the building was unsuitable because of insanitary surroundings and the confined space for convalescents. A photo of Barwon House, Mordialloc is seen in Figure 2.

The Health Officers for the shire, had visited Mrs O’Brien’s boarding house known as Barwon House and ascertained its suitability as an emergency hospital. They believed the building could be converted to a hospital with forty beds with minimal cost. The Council accepted the recommendations of the doctors, establishing the hospital with a matron, two trained nurses, three VADs and one orderly. Drs. Joyce and Scantlebury shared the duties of medical attendant.

By March 1919 auxiliary hospitals at Mordialloc and Sandringham had been closed down but in that month there appeared to be a resurgence of the disease. Three constables and a sergeant from the Brighton station were admitted to the hospital in the Wilson Reserve suffering from pneumonic influenza. Immediately the police station was quarantined and a disinfectant program commenced. Later that evening the constable who was assisting in this process was admitted to the hospital also suffering from influenza, making five out of a local force of eight of the station off with the ‘flu’.

By the end of 1919 the calamitous disease that had struck the world abruptly began to vanish. One suggestion for this state of affairs was that the disease had probably ran out of people who were susceptible and could be infected. Whatever the reason, people were pleased to learn that the danger of infection to themselves and others had passed.

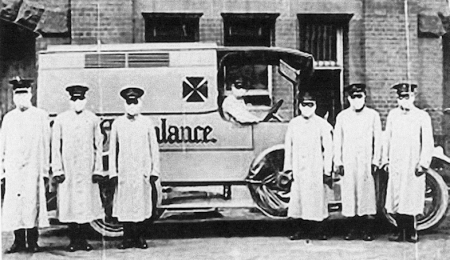

The precautions taken by Canadian members of ambulance staff (fully gowned, goggled, masked and wearing gloves) during the 1918-19 influenza epidemic are seen in Figure 3.

I wish to acknowledge that this an abridged version of that which appears on Graham J. Whitehead’s Website which greatly expands our knowledge of the influenza epidemic in 1918-19.